Galactic Empires for Networks (GEn) – a Swiss multiplayer game (1984-2000)

Von Beat Suter

Kann ein Strategiespiel 40 Jahre später noch gleichviel Spannung und Spielspass generieren? Kann ein Netzwerk-Spiel 25 bis 30 Jahre später auf neuen Systemen noch genauso gut funktionieren wie damals? Was unmöglich oder unwahrscheinlich klingt, schaffen drei Schweizer Entwickler mit ihrem Spiel Galactic Empires. Alle drei gehören zu der ersten Generation von Informatik Studierenden der ETH Zürich. Sie haben die Digitalisierung in der Schweiz von Anfang an mitgeprägt. Ihr Multiplayer Spiel hat eine Spieldauer von 4 – 8 Stunden und kann heute noch im gleichen Rahmen gespielt werden, wie damals, als sie mit Freunden ganze Nächte durchgezockt haben.

Der Hinweis kam von einem guten Freund, der in den frühen neunziger Jahren regelmässig Freitag- oder Samstagnacht ein Science-Fiction Strategiespiel in seinem Freundeskreis aus Informatik und Ökonomie gespielt hatte, meist in den Wohnungen und Büroräumen seiner Freunde. Dabei handelte es sich um ein Multiplayer Spiel, das über Jahre immer wieder weiterentwickelt und immer wieder gespielt wurde bis etwa ins Jahr 2008. Die Entwickler und Spieler bezeichneten das Spiel mit GalEmp oder Galactic Empires, später auch GEn, Galactic Empires for Networks.

1984

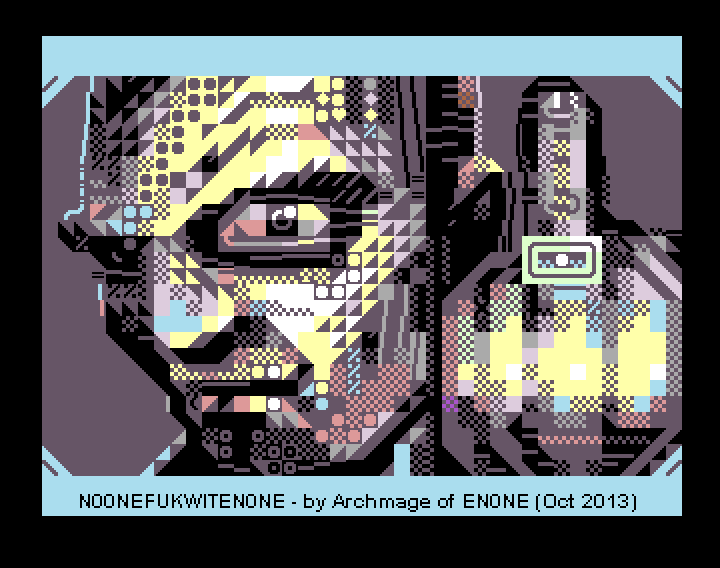

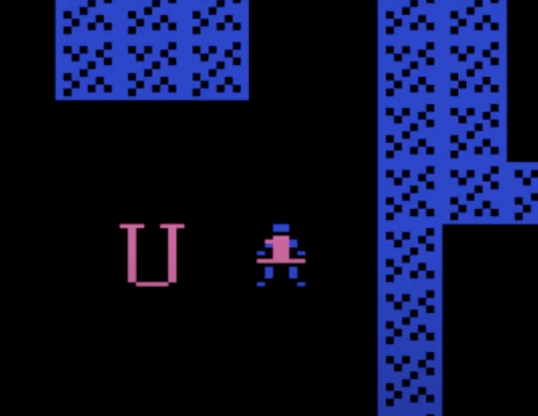

Eine erste statische Version des Strategie- und Simulationsmodells im Weltall wurde 1984 von Peter Vrkljan auf Apple II entwickelt. Der ETH-Student hattes es in Pascal neu programmiert (cf. Suter 2023). Peter Vrkljan lebte damals in Wettingen, Kanton Aargau, und hatte Ende 1982 mit dem Informatikstudium an der ETH Zürich begonnen. Er gehörte zum zweiten Jahrgang der Informatiker überhaupt. Vrkljan schrieb das Programm im Computerraum des Hauptgebäudes der ETH Zürich, der damals mit ca. 20 Apple II Maschinen ausgestattet war. Dort traf er auf Studierende älterer Semester. Einer davon war Peter Leikauf, den er noch vom Sportverein (Tischtennis) her kannte. Der andere war Jochen Walz, der ebenfalls in die Kanti Baden gegangen war. „Jochen war der Obergamer im Computerraum im [HG] Hauptgebäude der ETH Zürich”, wo Spielen verboten war. “Er schrieb auch das legendäre Druckprogramm, welches alle Studenten an der ETH benutzten”, erzählt Vrkljan (2023). “Wir spielten ein [Space-Simulations-] Game ein paar Mal, und ich beschloss ein benutzerfreundlicheres Spiel zu programmieren. 1984 war es fertig. Es hatte ca. 1500 Zeilen Code.” (ibid.)

Weiterlesen →